Welcome to my English 1302 Portfolio!

Welcome to my English 1302 Portfolio!

Category Archives: Uncategorized

A tale of two sentences: Faulkner and Hemingway

William Faulkner and Ernest Hemingway are obviously different in many ways. One is from Mississippi, the other from Northern Michigan. One’s writing is firmly anchored in one fictional county in the American South, the other’s writing spans the globe. But perhaps one of the most obvious differences between the two writing is in the formation of their respective sentences.

On the one hand, the sentences of William Faulkner are exceptionally long, complex, and characterized by the use of a vast vocabulary. Here’s a not-atypical example from “A Rose for Emily”:

For a long while he just stood there, looking down at the profound and fleshless grin. The body had apparently once lain in the attitude of embrace, but now the long sleep that outlasts love, that conquers even the grimace of love, had cuckolded him. What was left of him, rotted beneath what was left of the nightshirt, had become inextricable from the bed in which he lay; and upon him and upon the pillow beside him lay that even coating of the patient and biding dust.

Notice not only the length of the sentences, but also the somewhat archaic phrasing (“upon him and upon the pillow”) and large vocabulary (“cuckolded,” “inextricable”). These long, meandering sentences contribute to the gothic quality of Faulkner’s story, making them feel somehow ancient and more than a little spooky.

On the other hand, Hemingway prided himself on his short, to-the-point sentences that revealed only the essential details and left the rest up to the reader. For example:

Just then the hyena stopped whimpering in the night and started to make a strange, human, almost crying sound. The woman heard it and stirred uneasily. She dd not wake. In her dream she was at the house on Long Island and it was the night before her daughter’s debut. Somehow her father was there and he had been very rude. Then the noise the hyena made was so loud she woke and for a moment she did not know where she was and she was very afraid…

Hemingway’s language is quite barebones: just the facts, and nothing but the facts. He’s written elsewhere about writing being like an iceberg–what you see should be only the tip, with all of the emotions submerged beneath, for the reader to discover.

Which style of writing do you prefer most? Long, detailed sentences, or nothing but the facts? As we read more contemporary literature this semester, keep your eyes out and see if you can identify the influence of Hemingway or Faulkner in other works.

Sarty’s uncertain new world

I very much enjoyed seeing your detective work with “A Rose for Emily,” but it didn’t leave much time to discuss the other Faulkner story we read, “Barn Burning.” So, I wanted to post a few thoughts here.

For me, this story is very much about the relationship between the father and the son, and the son’s attempt to reconcile his desire to be close with his father and his desire to be moral and perhaps even accepted by society. Sarty’s father is a deeply troubled man, only able to resolve conflict through the ritual purification of burning other’s property. On the other hand, he constantly reminds Sarty that the only ties that really bind are those of blood.

The first time in the story that the father burns a barn, Sarty almost tells the truth, but is saved at the last minute from confessing. After this, Sarty hopes in vain that his father has learned a lesson, or that somehow the splendor of the new plantation house will be enough to convince his father to desist. But of course the barn must burn again, after the rug incident, and Sarty this time runs to the house to tell de Spain what’s happening.

As a result, he ends up fleeing into the woods. He is totally lost, no longer a part of his own family, but with nowhere to turn to. In this sense, I find it to be a pretty depressing story. He has chosen to act morally, but what does he have to show for it?

Modernist poetry in a post-Spring Break world

Getting back into the swing of things after Spring Break can be a challenge for everyone…professors included. After a challenging but rewarding week caring for my father in Ohio, I came back to a mountain of grading, courses to plan, and a non-functional phone and car. On the other hand, it’s great to be back in the Valley, where I can walk outside without losing my ability to feel my nose, and to see all of my students again.

If, like me, any of you are behind on your blogs coming out of break…now’s a good time to get caught up before you get too far behind! We’ve begun discussing Modernist poetry, and note: you don’t have to post on each and every poem. Instead, I’d encourage you to choose a few poems to concentrate on so you can get more in depth in your analysis. Next week, we’ll be looking at Faulkner and Hemingway, so you’ll only have one work for each class to look at.

I know that for many reading Modernist poetry can be a daunting experience. So many allusions! So many seemingly disconnected images! So weird!

I suspect that some of you whose natural tendencies lean toward anarchy and disorder (you know who you are) may really enjoy the modernist poets we’ve read in class. For those of us who feel trapped in schedules and societal norms, there’s something refreshing about breaking free from traditions and structures. On the other hand, for those who crave order in their lives (and their literature), and hunger for meaning and explanation, modernism can be frustrating.

In either case, I hope you can enjoy the fun that the poets we’re reading have with language…and the challenge of creating your own interpretations when no obvious interpretations present themselves.

Walt Whitman, revolutionary

As I’m reading through “Song of Myself” in preparation for class tomorrow, I can’t help but be struck all over again by just how revolutionary Walt Whitman is as a writer. It’s not just the free verse–though that’s a big part of it. It’s not even just the frank discussions of sex, and the celebration of physical pleasures–though that’s a big part of it, too. For me, it’s just the sheer freedom he embodies. He seems to be saying: I will talk about everything and anything I please, and I will love everything and anything I please. So be it!

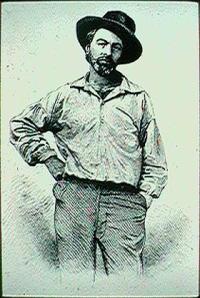

Even the picture of Walt Whitman that appeared in the original edition of Leaves of Grass was revolutionary--no shirt and tie here!

One concept that I think can be useful in understanding Whitman is his belief–influenced by Hinduism–in the “over-soul.” Basically, the over-soul is an idea that the souls of all creation–people, animals, plants, bacteria, everything–are connected spiritually (this idea was very popular with the movement called Transcendentalism, of which Whitman was a part). The over-soul is kind of like God–if you think of God as residing in living things on Earth. Or, in other words, as God being everywhere.

If the over-soul is in all living things, then it follows that all living things are at a certain basic level equal. Men and women, white and black, even human and non-human–everyone is composed of the same spiritual material. This belief is linked to Whitman’s overriding belief in the potential of democracy–and his desire to create a new kind of poetry that is truly democratic in nature and that binds together all of the diversity of the United States.

Anyway, those are a few thoughts to get us started. I know Whitman is hard–but at least for me he can also be exciting in his no-holds-bar approach to poetry.

Huck Finn, new and improved!?

We’ve touched on briefly the controversy over a new edition of Huck Finn that replaces offensive language with more acceptable versions; “nigger” is replaced with “slave”; “Injun Joe” by “Indian Joe,” etc. The argument made by the book’s editor is that the offensive language prevents high school teachers and students from reading what otherwise might be an interesting novel to study. Critics, though, charge that the new edition at best is a money-making scheme, and at worst “sanitizes” history by leaving out language that is a continuing record of the racism of an era. Here’s an article from Mark Twain’s hometown newspaper about the controversy. As well as the editor’s defense of the book, and an African-American critic’s commentary. What do you think? Is this a justifiable change, or not?

The “conscience passages” in Huck Finn

Several of you have mentioned in class that one of the reasons Mark Twain might have chosen to write the book from Huck’s first-person point of view is that the book becomes a coming-of-age-novel–with Huck perhaps standing in for a country that is also coming of age in the years immediately before and after the Civil War. In this reading, it’s important to notice the ways that Huck develops (or doesn’t develop, depending on your reading) as a moral person as he and Jim travel down the river.

This might be an interesting topic to post about on your blog: Do you feel that Huck “grows up” as the novel progresses? Why or why not?

Here are some passages from the novel that might be of interest as you reflect:

After the incident in the fog:

It was fifteen minutes before I could work myself up to go and humble myself to a nigger–but I done it, and I wanrn’t ever sorry for it afterwards, neither. I didn’t do him no more mean tricks, and I wouldn’t done that one if I’d a knowed it would make him feel that way.

Near the Ohio River at Cairo, Illinois:

Jim said it made him all over trembly and feverish to be so close to freedom. Well, I can tell you it made me all over trembly and feverish, too, to hear him, because I begun to get it through my head that he was most free — and who was to blame for it? Why, me. I couldn’t get that out of my conscience, no how nor no way. It got to troubling me so I couldn’t rest; I couldn’t stay still in one place. It hadn’t ever come home to me before, what this thing was that I was doing. But now it did; and it stayed with me, and scorched me more and more. I tried to make out to myself that I warn’t to blame, because I didn’t run Jim off from his rightful owner; but it warn’t no use, conscience up and says, every time, “But you knowed he was running for his freedom, and you could a paddled ashore and told somebody.” That was so — I couldn’t get around that noway. That was where it pinched. Conscience says to me, “What had poor Miss Watson done to you that you could see her nigger go off right under your eyes and never say one single word? What did that poor old woman do to you that you could treat her so mean? Why, she tried to learn you your book, she tried to learn you your manners, she tried to be good to you every way she knowed how. That’s what she done.”

After Huck writes the letter to Miss Watson:

So I was full of trouble, full as I could be; and didn’t know what to do. At last I had an idea; and I says, I’ll go and write the letter – and then see if I can pray. Why, it was astonishing, the way I felt as light as a feather right straight off, and my troubles all gone. So I got a piece of paper and a pencil, all glad and excited, and set down and wrote:

Miss Watson, your runaway nigger Jim is down here two mile below Pikesville, and Mr. Phelps has got him and he will give him up for the reward if you send. Huck Finn.

I felt good and all washed clean of sin for the first time I had ever felt so in my life, and I knowed I could pray now. But I didn’t do it straight off, but laid the paper down and set there thinking – thinking how good it was all this happened so, and how near I come to being lost and going to hell. And went on thinking. And got to thinking over our trip down the river; and I see Jim before me all the time: in the day and in the night-time, sometimes moonlight, sometimes storms, and we a-floating along, talking and singing and laughing. But somehow I couldn’t seem to strike no places to harden me against him, but only the other kind. I’d see him standing my watch on top of his’n, ‘stead of calling me, so I could go on sleeping; and see him how glad he was when I come back out of the fog; and when I come to him again in the swamp, up there where the feud was; and suchlike times; and would always call me honey, and pet me, and do everything he could think of for me, and how good he always was; and at last I struck the time I saved him by telling the men we had smallpox aboard, and he was so grateful, and said I was the best friend old Jim ever had in the world, and the only one he’s got now; and then I happened to look around and see that paper.

It was a close place. I took it up, and held it in my hand. I was a-trembling, because I’d got to decide, forever, betwixt two things, and I knowed it. I studied a minute, sort of holding my breath, and then says to myself:

“All right, then, I’ll go to hell” – and tore it up.

By the way, many critics have argued that this last passage is the climax of the novel. What do you think?

How do you read (and see) Jim?

Today in class, we started discussing the character of Jim, and some of the controversies that exist regarding how his character is portrayed. On the one hand, many critics charge that he is a “flat” character who conforms to the many of the racial stereotypes of African-American slaves that existed at the time and persist even to the present day (you might think about how African-Americans are depicted in movies and/or TV shows that you’ve seen, such as the John Wayne movies that Bill mentioned in class). On the other hand, defenders of the novel often assert that Jim is “wearing a mask”; i.e. he acts in certain ways (such as his superstitions) in order to accomplish his objective of staying free. For certain, he needs Huck as his protector, and he will do anything in his power to keep him by his side.

As you post this week and next–and as we read several articles from different viewpoints in class–I’d be curious to hear the class weigh in with thoughts on this issue. Also, you might check out this website that highlights different images of Jim that have appeared in various editions of Huck Finn over the years. You can see very clearly how some artists have been influenced by the racial stereotypes, while others emphasize Jim’s compassion or his father-like qualities.

Frederick Douglass’s Narrative: The Aftermath

Here is a link to the response to Frederick Douglass’s Narrative that was written by a friend of Covey’s. And here is Frederick Douglass’s response to the response. As you read, notice the arguments that are made in the slaveholders’ defense, which might remind you of our discussion of apologists for slavery in class. And see how Frederick Douglass addresses each of these arguments head on in his response.

Frederick Douglass on the Web

I’m passing on a few links about the life and times of Frederick Douglass, which might be useful in establishing the context for your reading. Here’s a virtual museum exhibit from the Frederick Douglass National Historic Site, with lots of photos and artifacts from Douglass’s home. Here’s a link to a very well-designed site with background information about the abolitionist movement. And last, here’s an interesting PBS series that examines the history of race as idea.

As you’re reading the Narrative, you might think about a couple of questions. Who do you think that Douglass’s audience was when he wrote the book? What assumptions or questions might this audience have had about slavery and/or race in America? How does he address these questions? I’ll look forward to talking about these things–and more–in class on Monday.